INTERACTION AND

INTERDEPENDENCE

Species are both dependent

and compete with each other, which leads to a fragile equilibrium.

The incredible biodiversity of the rainforest renders the equilibrium

extremely complex.

The basic idea is that each specie, however modest, has its importance

in the general equilibrium and represents just one link in an immense

chain…

Example : pollinization

Most flowering plants of these regions totally depend on insects,

birds and bats for their survival : the rainforest's density renders

wind pollinization inefficient, except perhaps for the very large

dominant trees.

|

|

|

Another example : that of the

atta type leaf-cutting ants (more than 200 species). They live in

colonies of up to 5 million individuals. They cut the leaves of

certain trees (not all…) and bring them under the earth. They

"cultivate" on these leaves a mushroom on which they feed.

This mushroom does not exist elsewhere in nature. It can digest

the leaf cellulose, something the ants are incapable of doing. The

ant cannot exist without this mushroom, which does not exist without

ants…

(A large tree, "hymenaea courbaril", has developed an

original protection to prevent the atta ant from denuding if of

its leaves : it contains elements which are toxic not for the ant

but for the mushroom !). The ecological impact of the attas is considerable.

They manage to form true 20 cm large "highways" on the

ground. Studies have shown that they consume by themselves as much

foliage as all the herbivorous vertebrates of the rainforest.

|

Last example even more fascinating

: Another specie of ants, pseudomyrmex ferruginea, lives on certain

acacias. They systematically attack any "visitor" (insect

or human hand). But they also cut with their mandibles plants that

start to grow on or above the tree and which might hinder its growth.

As a counter part, the acacia has developed cavities to shelter

ants and also secretes a nectar to feed them !

|

DEFENCE MECHANISMS

AND MIMICRY PHENOMENA

Nearly every specie has its

predator and each one has developed means of defense against them.

Before fight or violent confrontation, one of the principal means

of defense is to become undetectable. That is why you have the impression

that the forest is empty.

The mimicry phenomena are fascinating :

. Certain species disguise themselves to escape from predators (defense

mimicry).

. Others try to become undetectable by their eventual prey (offensive

mimicry).

. Often both kinds of mimicry are found in the same specie…

A perfect example of defense

mimicry is found in the phasms, these insects look exactly like

twigs.

Mimicry is never absolute,

it is always relative to the surrounding environment of the animal

or to certain of its elements. The coat of jaguar for example: its

black-spotted yellow looks garish against the cement of the Zoo

on which the animal rests. But believe me, in the forest, the camouflage

is very efficient. Most territorial animals of the rainforest are

nearly undetectable IF THEY ARE NOT MOVING.

How have they become so adapted

to their surrounding environment?

|

|

|

|

This is what the THEORY OF THE EVOLUTION

OF THE SPECIES, developed in the second half of the 19th Century by Charles

Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, tries to explain. Both stayed for a long

time in the Amazon zone and found there many sources of inspiration.

Schematically, within a specie, certain individuals have certain characteristics

that make them more apt to survive than others in a similar environment:

for example, the darker an animal is, the less detectable will it be against

a dark background.

From then on, the darker individuals have an advantage … being less

susceptible of being seen by predators, their number will tend to increase

proportionately and the "dark" gene will become progressively

dominant.

This evolution occurs sometimes "relatively" fast. One of the

best known cases is that of a butterfly. Following the 19th Century industrial

revolution and the smoke it generated, some specimen of this specie, originally

light grey, have become nearly black!

In Amazonia, this adaptation can be totally fascinating:

For example, an extraordinary

case of offensive mimicry: certain small spiders feed exclusively

on ants.

Their body has evolved to strikingly resemble the body of one of

these insects:

The cephalothorax (the characteristic thorax/head unit of arachnidae)

has divided itself in order to make believe there is a head.

The first pair of legs has lost its ambulatory function to simulate

a pair of antenna.

Thus these spiders can become undetectable by ants.

|

|

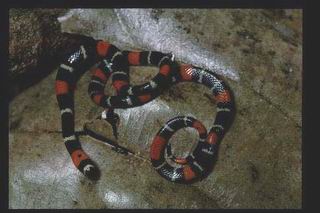

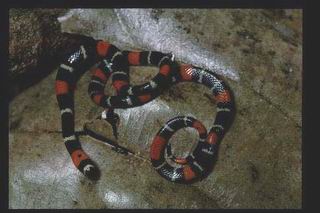

Other cases, this time of defensive mimicry, concern many harmless animals

imitating aggressive or poisonous species.

Certain butterflies resemble wasps so much that you cannot tell them apart.

Certain grass snakes imitate perfectly the spectacular skin of a very poisonous

coral snake specie.

These examples are relatively simple.

The mimicry phenomena can be much more complex in their relation to the

surrounding environment.

A study on the butterflies of Peru has shown that a specific colour of wings

corresponds to different strata of the great rainforest:

From ground level up to 2m high : the "transparent" zone : transparent

wings with black streaks.

From 2 to 7m high : the "tiger" zone : wings streaked with yellow,

brown, black and red.

From 7 to 13m high: the "red" zone: red is the dominant wing colour.

From 15 to 30m high: the "blue" zone.

From 30m to the canopy: the "orange" zone.

These are the dominant tendencies,

of course, and it does not mean that no blue butterflies will be found near

the ground! But the hypothesis being defended is that each "complex"

or "colour" corresponds to the best camouflage of the butterfly

when it flies, according to light conditions in the different forest strata.

More rarely, instead of mimicry, certain species "choose" to deliberately

attract attention by loud colours, generally based on yellow, orange and

red, to warn the predator of the danger they represent in case of attack.

These are generally poisonous or venomous species. In this case, it calls

upon the genetic memory of the aggressor.

Two splendid examples:

-The

coral snakes (micrurus sp)

-The

coral snakes (micrurus sp)

-The

dendrobate frogs (their skin secrete an extremely active venom).

-The

dendrobate frogs (their skin secrete an extremely active venom).

Unfortunately for the amateur photographer, coral snakes and dendrobates

are shy creatures, they hide most of the time in the humid ground cover

of the forest or under dead wood.

Finally, certain batrachians, reptiles

or insects show "flash" colours, with the aim of "blinding"

or momentarily impressing an aggressor thus giving them time to flee. "Agalychinis

Callydrias", a small tree-climbing frog of Central America has for

example large brilliant red eyes. It stays usually on leaves with closed

eyes. When it opens them, the effect is surprising!!

As a conclusion on mimicry, there are

mysteries!

Take for example the case of

the large macaw, linked to the parrots:

They are large and highly coloured.

They belong to the rare loud animals of the great rainforest. I

will even say VERY loud!

These animals make no effort to hide, I therefore thought that they

had no predator. How wrong! I once saw a great harpy eagle "murder"

one of these birds.

All this is fascinating, you will tell me, but a little discouraging.

Is there no chance of seeing wild animals in the rainforest?

There is, of course but YOU HAVE TO PUT ALL LUCK ON YOUR SIDE BY

LEARNING TO BEHAVE ADEQUATELY IN THE SURROUNDING ENVIRONMENT.

You know now that a walk through the forest is no safari. Any passive

attitude will be sanctioned by failure. You have to stay concentrated,

make great efforts of attention…

First of all, there are AUSPICIOUS HOURS, and those that are not.

At the height of the heat, animals limit their moving about. Prefer

the morning or the end of afternoon.

Birdwatchers know it, it is

necessary to get up early.

|

|

|

|

Learn to use all your senses, in particular

hearing and smelling. As has been shown, it is rare to localize an animal

by sight.

LISTENING IS FUNDAMENTAL :

First of all, some species, very hard

to see at first sight, can be localized by their cry. I have spoken of the

macaws, in fact, the discordant cries of all parrots can be heard from rather

far.

The shrill whistling of the large toucans is easily recognizable.

|

|

A small bird, the screaming

piha (lipaugus vociferans) has what might be called a very characteristic

song (!) that you will hear very often…the males spend three

quarter of their time calling the females.

One of the most characteristic

sounds of the great rainforest is the cry of the howler monkey (alouatta

sp) : it is somewhat similar to the sound of the wind during a raging

storm.

These howls can be heard kilometres away and are very impressive

when close by.

They are due to a sort of goitre that these monkeys have and which

serves as resonance chamber.

|

Among insects, the sound of innumerable cicadae can be deafening…

Among insects, the sound of innumerable cicadae can be deafening…

At

night, the batrachians take their turn, certain species can prevent you

from sleeping : one day, I camped under a large tree in the south of Venezuela.

Shortly after sundown, a true concert of tree-climbing frogs started above

our heads.

At

night, the batrachians take their turn, certain species can prevent you

from sleeping : one day, I camped under a large tree in the south of Venezuela.

Shortly after sundown, a true concert of tree-climbing frogs started above

our heads.

The Ye'Kwana Indian chief who accompanied me got up from his hammock, requisitioned

a young Indian and showed him the tree. The next morning, the boy proudly

showed us the culprits : he had not killed them but had captured them and

had carefully tied them together with fine lianas. The chief ordered him

to liberate them… This small anecdote gives you an idea of the psychology

of the Indians, a subject that I will treat later.

All these are sounds that hardly go unnoticed.

In most cases, you will have to listen carefully to hear the slightest sound…

The slightest rustle of dead leaves can mean a reptile on the ground, a

creak above you, a monkey in a tree.

The other senses

THE USE OF SMELLING IS ALSO FUNDAMENTAL

Some species smell strongly, either

directly like the wild pigs, or indirectly through their urine, like the

howler monkeys and the felines that mark their territory like this.

The only time I encountered a giant

armadillo (priondontes maximus), a rare nocturnal specie that can attain

60kg, I mostly heard him dragging himself along dry leaves and I smelt him!

The animal really stank!

SIGHT

No need to open your eyes wide

to look at what passes as a horizon, your chance of directly seeing

an animal is just about nil, but try to notice traces. When I speak

of traces, I don't mean only tracks on the ground, but also the

secondary manifestations of animal presence :

The foliage which moves a few meters ahead of you.

Branches that move in a tree in front. That is why it is simpler

to see monkeys if there is no wind…

|

|

|

Similarly, if you pass through

a place littered with fruit, look carefully in the trees and around

you, there is a strong chance that a fruit-eating animal, mammal

or bird, is hiding nearby.

As a corollary, during hikes :

Don't speak continuously

to your guide. It is he who, most of the time, will spot the animals

that you will see. If he has to turn around every 30 seconds or

so, he will not be able to do his work correctly. Needless to say

that if you spot, hear or smell something interesting, you must

share it with your group, but keep questions of general interest

for later, if need be, write them in as small notebook.

Walks in the forest are usually done on narrow trails, single file.

Your guide must be at the head, for it is he who is most apt to

spot a snake coiled up on the trail.

Don't stay too close so as not to hamper him, especially if he has

to use his machete often, but don't stay too far either. Seeing

an animal is generally furtive, a few seconds or less (I am not

speaking of invertebrates).

|

|

|

If you are too

far, you will be told "I just saw an agouti, but he escaped

quickly" or "you just missed a group of spider monkeys"

and other frustrating remarks because you will not have seen anything.

|

|

If there are many of you, organize

rotations in order not to have always the same one be behind the

guide.

Be patient, don't get discouraged, try to remain in a state of concentration,

even if the walk is long. I remember guiding a hike that lasted

three days during which we saw nothing. The last evening, I offered

a night walk. During two hours, we saw nothing. Coming back to the

place where we had left our dug-out canoe, I found myself face to

face with a superb puma, not intimidated at all. I made desperate

signs towards the rear to try to attract the attention of my companions

but they were at least 50m away, in the process, I presume, of telling

each other about their last beach week-end. When they arrived at

last, the animal had of course disappeared!

My personal experience has

shown me that, in a group, it is always the same ones who see something,

and always the same ones who see nothing!

Remember however that even with the best intentions in the world,

the chance factor is important and the fact of having purchased

an organized tour does not give you a guarantee of meeting animals.

The rainforest is mostly an atmosphere. It is in the Zoo that you

will see the animals best from close!

|

|

-The

coral snakes (micrurus sp)

-The

coral snakes (micrurus sp) -The

dendrobate frogs (their skin secrete an extremely active venom).

-The

dendrobate frogs (their skin secrete an extremely active venom).

![]() Among insects, the sound of innumerable cicadae can be deafening…

Among insects, the sound of innumerable cicadae can be deafening…![]() At

night, the batrachians take their turn, certain species can prevent you

from sleeping : one day, I camped under a large tree in the south of Venezuela.

Shortly after sundown, a true concert of tree-climbing frogs started above

our heads.

At

night, the batrachians take their turn, certain species can prevent you

from sleeping : one day, I camped under a large tree in the south of Venezuela.

Shortly after sundown, a true concert of tree-climbing frogs started above

our heads.